This blog post presents an imagined day in the life of a Pompeii citizen named Lucius in the year 79 AD, just before the eruption of Mount Vesuvius. While inspired by historical facts and daily life in ancient Pompeii, the events and characters described are fictional, and images are imagined scenarios created to offer a vivid glimpse into the everyday experiences of this ancient Roman town.

.

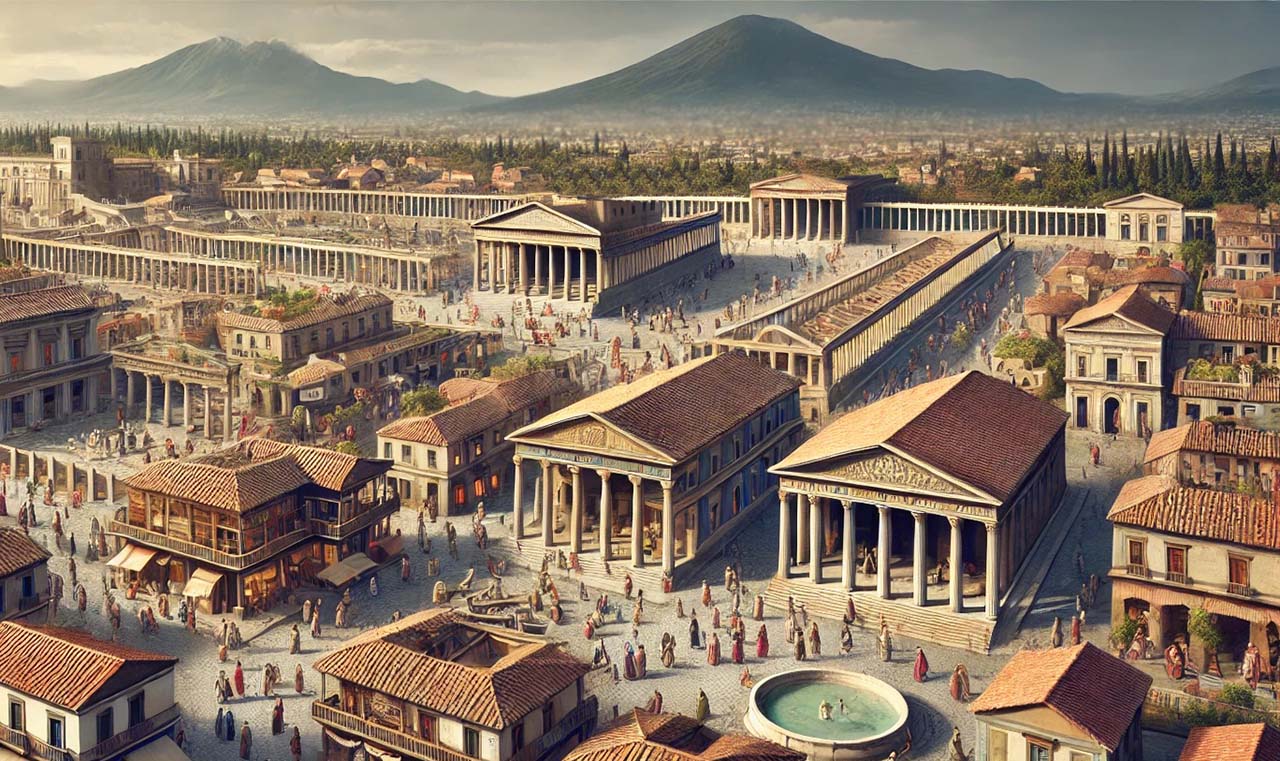

It is AD 79 in the ancient Roman city of Pompeii, nestled in the shadow of Mount Vesuvius. For now, life goes on, as it always has, beneath the shadow of Mount Vesuvius.

Dawn in Pompeii – Year 79 A

Lucius, a middle-class merchant, slowly stirs from sleep as the first light floods his room. His bed creaks slightly as he rises, made of simple wood but with a mattress stuffed with straw and wool—a far cry from the luxury of the Roman elite, but enough to provide a decent night’s rest. His home, like many in Pompeii, is modest yet comfortable. The bed is draped with a woolen blanket, slightly worn but warm, and the cool tiles underfoot offer a refreshing contrast as Lucius steps onto the floor.

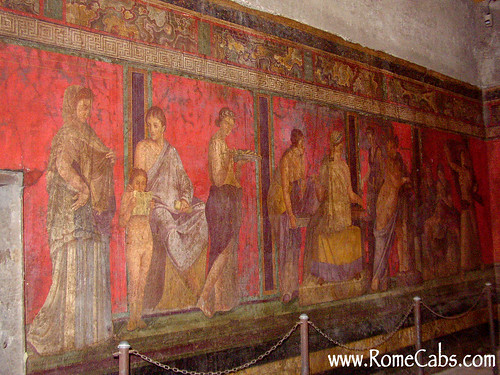

His home, a domus typical of Pompeii’s working class, is modest but comfortable, reflecting both functionality and touches of the vibrant artistic culture that permeates the city. The walls of the bedroom are adorned with frescoes in shades of deep red and ochre, depicting scenes of mythological creatures and pastoral landscapes.

These frescoes, though not as grand as those in the villas of the wealthy, speak to the town’s devotion to art and beauty. The delicate brushstrokes and intricate patterns remind Lucius daily of Pompeii’s flourishing creativity.

As Lucius moves from his bedroom into the central atrium, the heart of the home, the day’s promise of warmth is already palpable. The atrium, illuminated by the soft morning light, is an open space that serves multiple purposes. The floor is paved with intricate mosaics, their small, colorful stones pieced together to form geometric designs and symbolic patterns.

The centerpiece of the atrium is a shallow pool known as the impluvium, which collects rainwater that falls through the open roof above. This pool not only provides water for household use but also cools the home on hot summer days. Around it, columns frame the space, adding a sense of grandeur to an otherwise simple house.

Lucius dresses in his usual attire—a tunic of undyed linen, tied at the waist with a simple leather belt. His sandals, worn from countless walks along Pompeii’s well-trodden streets, sit beside the doorway. Before leaving his room, he catches a glimpse of himself in a polished bronze mirror, adjusting the folds of his tunic with a quick, practiced hand. The reflection offers a momentary pause in his routine, reminding him of the passing of time and the constancy of his daily life.

The kitchen, though small, is a hub of activity as Aemilia, his wife, prepares the family’s breakfast—ientaculum. The kitchen, like the rest of the house, is modest but efficient, with clay pots lining the shelves, and a hearth where Aemilia bakes bread.

The scent of freshly baked panis fills the room, mixing with the sharp, earthy aroma of the pecorino cheese that sits on the wooden table. She places a handful of fresh figs from their garden into a bowl—simple but flavorful fare.

Outside, in their small courtyard garden, the gentle rustling of leaves adds to the peaceful ambiance. The garden is filled with aromatic herbs like rosemary and thyme, alongside fig and olive trees, their gnarled trunks a testament to their age and resilience. The air is sweetened by the perfume of flowering vines that climb the walls, and bees hum softly as they flit from flower to flower.

After breakfast, Lucius takes a moment for a quiet ritual of devotion. In an alcove near the atrium stands the lararium, the family’s household shrine. Here, tiny statues of protective gods—the lares and penates—are arranged alongside figures of ancestors. The shrine is simple yet sacred, with offerings of fruit and wine placed beneath the statues.

Lucius approaches reverently, his head bowed. He whispers a brief prayer for protection and good fortune, his fingers lightly grazing the smooth marble statues. His gesture is one of tradition and hope—a daily ritual that links his family to the divine, a connection that is essential to the rhythm of Roman life.

With his prayer complete, Lucius raises his hand in offering, placing a small piece of bread on the altar. For a moment, the world feels still, as if his petition to the gods has created a pause in the flow of time. The faint sound of the impluvium’s trickling water fills the space, soothing and eternal, a reminder that while the gods may watch over them, the elements remain ever-present in their lives.

Morning ushers the Bustle of Pompeii

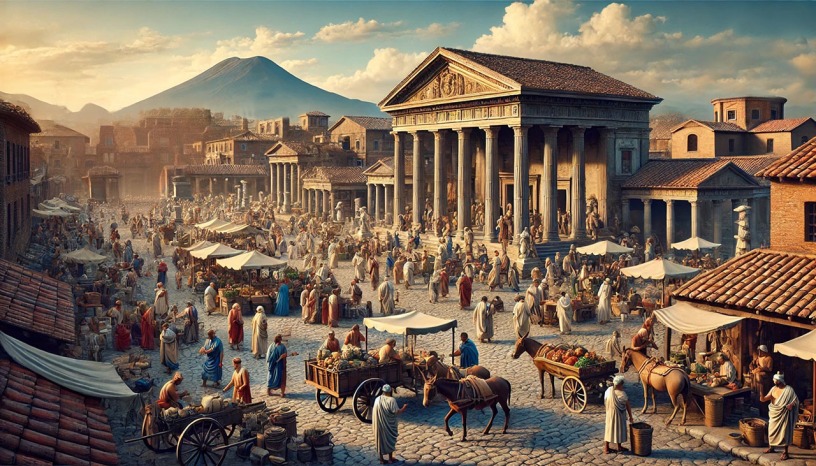

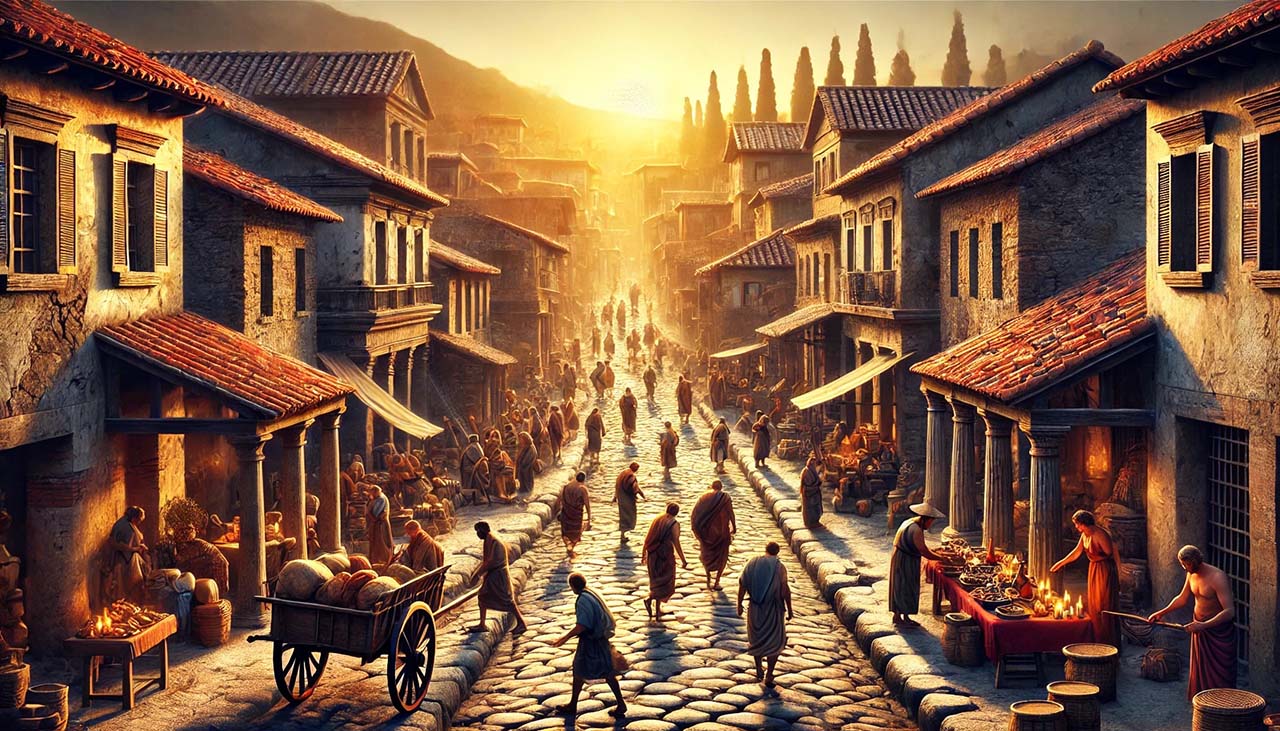

As the sun climbs higher casting a golden hue over the red-tiled rooftops, Pompeii truly awakens. The rhythmic shuffle of sandals and the creak of wooden carts on cobblestones mark the town’s heartbeat, echoing off the tightly packed buildings that line the streets. Craftsmen, traders, farmers, and slaves weave through the labyrinth of Pompeii’s bustling lanes, their faces set with the determination of a new day’s work.

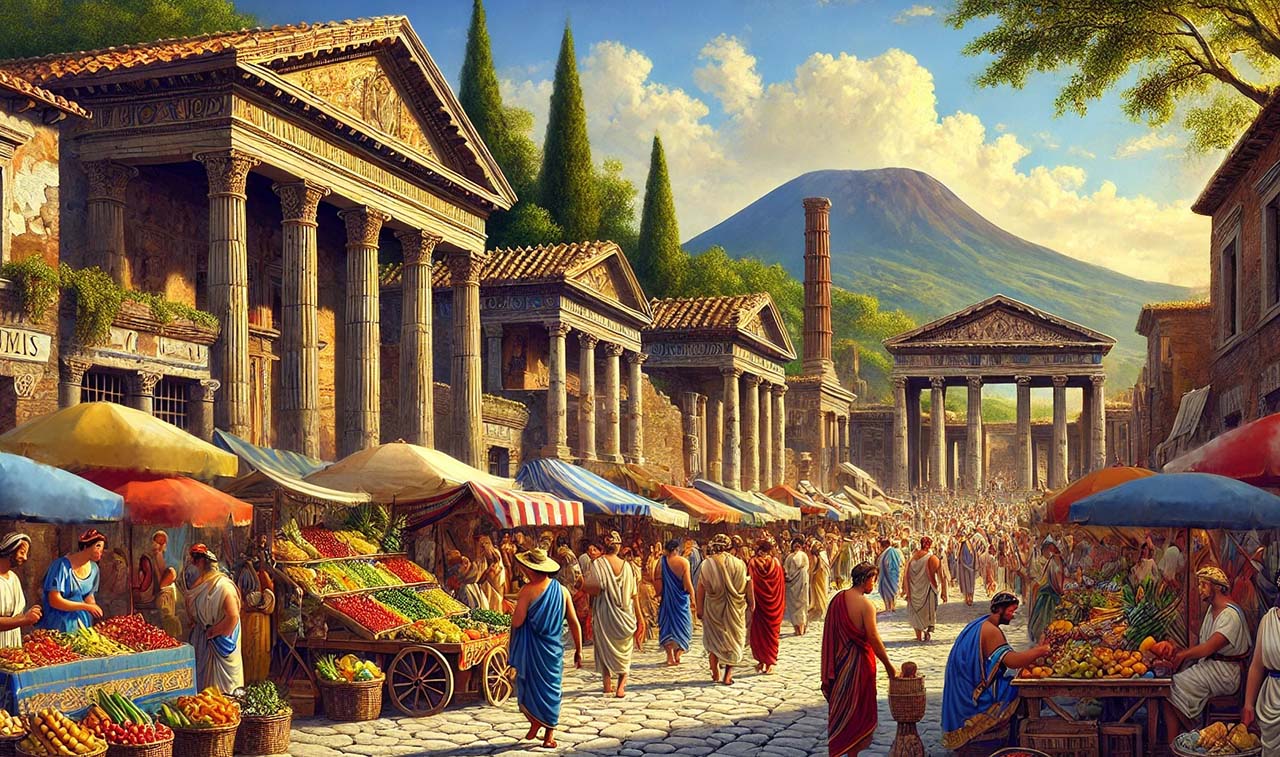

The market district, centered along the Forum, hums with life. Pistrina (bakeries) churn out the day’s bread, the smell of freshly baked panis wafting through the air, mingling with the earthy aroma of herbs and spices from nearby stalls. Slaves, burdened with baskets of fruit, vegetables, and grain, haul goods to market stalls.

The cries of vendors fill the air, each calling out their wares in a melodic cacophony: fresh fish from the nearby coast, plump olives, pungent garlic, and ripened figs. It’s a sensory feast—one that is repeated daily, yet never tiresome to the inhabitants of Pompeii.

The walls are lined with large amphorae, their rounded clay surfaces stacked carefully with goods—olive oil and wine, the staples of Roman life. The air is thick with the sweet, earthy scent of these goods, mixed with the faint tang of salt from the nearby sea. As Lucius arranges his wares, the early morning rush begins, with familiar faces stopping by for their daily supplies.

Regular customers greet Lucius with the ease of long-standing relationships. A friendly exchange of pleasantries is followed by the haggling that is part and parcel of the market’s routine. Today, a young noblewoman named Flavia stops by, her flowing stola brushing against the floor as she inspects the amphorae of oil for an upcoming feast. She speaks in soft tones, her personal slave trailing behind with an empty basket ready to be filled. Nearby, a fisherman offloads his early morning catch at the adjacent stall—gleaming fish still wet with the spray of the sea, their silver scales reflecting the sunlight.

Pompeii’s market is more than just a place of business; it is the social heart of the town. The streets, lined with popinae (taverns) and thermopolia (small eateries), are filled with people of all classes—nobles, freedmen, and slaves—mingling together, sharing stories and the latest news. Lucius, like many of his fellow merchants, is as interested in the gossip as he is in the day’s sales. Here, news travels quickly: rumors from distant Rome, whispers about the latest political developments, and tales of the gladiatorial games that bring excitement to the amphitheater.

Today, the talk is of the strange tremors that have been unsettling the ground beneath their feet. “The gods must be angry,” an elderly merchant mutters as he examines a piece of fruit. Lucius chuckles, dismissing the man’s concern with a wave of his hand. The mountain—Mount Vesuvius—has slept for centuries, its presence looming but benign. “It’s nothing,” Lucius reassures him. “The earth is restless, but it will pass.”

His shop, modest but well-stocked, is filled with large clay amphorae of olive oil and wine. The sweet, earthy scent of these goods is strong in the warm air. As Lucius arranges his wares, regular customers begin to stop by, exchanging pleasantries and haggling over prices. Today, a young noblewoman, Flavia, is purchasing oil for the evening’s feast, while a fisherman offloads his catch at the stall across the street.

Pompeii’s market is more than just a place of business; it’s the beating heart of the town’s social life. Here, Lucius hears the latest gossip: rumors from Rome, news of gladiatorial games in the amphitheater, whispers about the strange tremors that have been unsettling the ground beneath their feet. “The gods must be angry,” an elderly merchant mutters, but Lucius dismisses the notion with a laugh. Vesuvius has slept for centuries, and surely, it will continue to sleep.

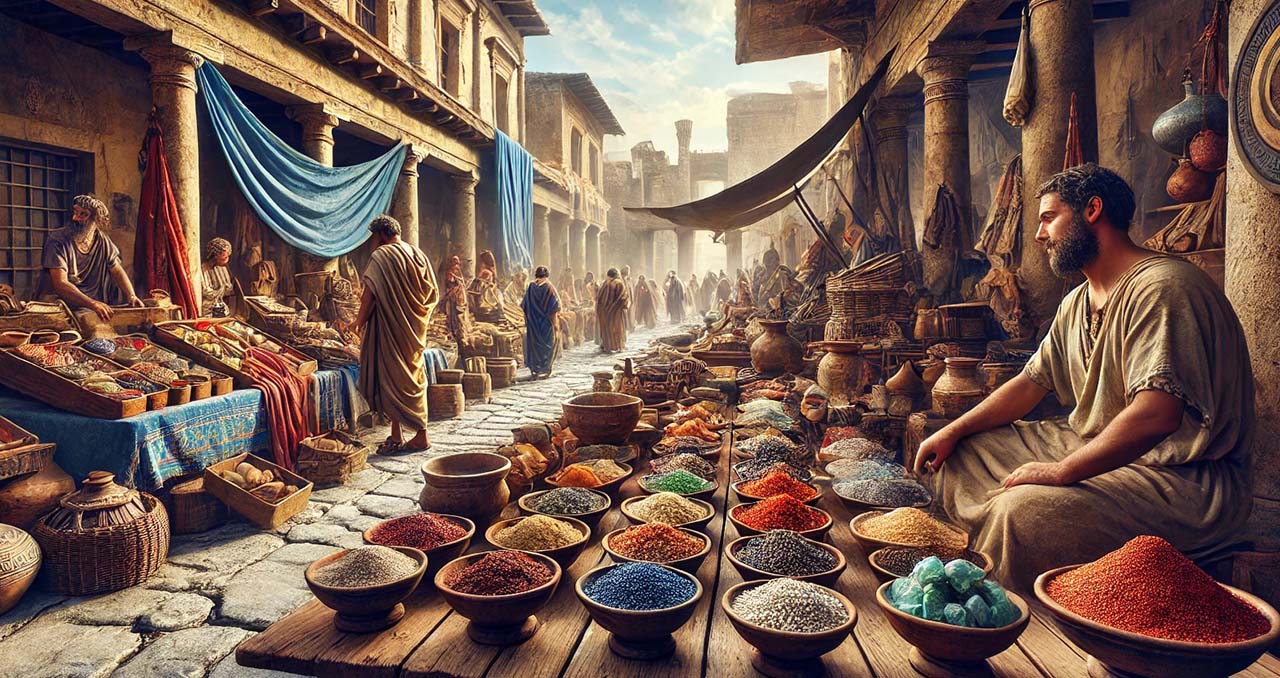

Yet the market buzzes with a different kind of energy as well, one driven by the exotic goods brought in from across the Roman Empire. Stalls are filled with rare spices from the East, their pungent fragrances filling the air: cinnamon, cardamom, and cloves.

Silk, shimmering with vibrant colors, drapes across tables, its softness enticing passersby. Polished gemstones, glinting in the sun, sparkle like tiny treasures. Lucius often marvels at how far these goods have traveled—across deserts and seas, through the vast expanse of the Empire, to finally rest here in Pompeii.

As the town crier’s voice rings out over the din, announcing upcoming events, the crowd’s attention momentarily shifts. A grand spectacle is promised at the amphitheater: a venatio—a wild animal hunt. Lions and tigers, imported from the far corners of the Empire, will be pitted against seasoned gladiators in a contest of life and death. The crowd murmurs with excitement, the promise of bloodshed and bravery drawing their interest.

Lucius listens, nodding to himself. Business might slow in the afternoon as many flock to the amphitheater to witness the spectacle, but for now, the day’s commerce takes precedence. He smiles as another customer steps into his shop, the familiar hum of Pompeii’s vibrant life filling his ears. It is a town that thrives on routine and spectacle, its people bound by the pulse of trade, gossip, and entertainment. And as Lucius goes about his work, the rhythm of Pompeii beats on, unaware of the fate that soon awaits it.

Midday in Pompeii: A Visit to the Baths

As the sun climbs higher in the sky, the heat of the day intensifies. By midday, it’s time for a break, and like many Pompeians, Lucius heads to the public baths. The baths in Pompeii, like those throughout the Roman world, are not just a place to clean oneself but also a center of social and recreational life.

Lucius heads to the Stabian Baths, his preferred spot in the city. This grand complex, among the oldest and most impressive in Pompeii, has stood for centuries, its architecture a testament to the Roman mastery of both form and function. The baths are more than just a place to bathe; they are the heart of Pompeii’s social scene, a hub where citizens gather to unwind, gossip, and escape the scorching midday heat.

Upon arrival, Lucius enters the palaestra, a large open courtyard bordered by elegant columns. This outdoor space, designed for exercise and physical activity, is where young men spar in wrestling matches or toss around a weighted ball. Lucius exchanges friendly words with a fellow merchant, their conversation drifting between business, politics, and the day’s events. Even at the baths, the pulse of Pompeii’s vibrant life is felt.

Lucius heads into the apodyterium, the changing room. The room is lined with marble benches and small cubbyholes where patrons store their belongings. Slaves, tasked with assisting their masters, help Lucius out of his tunic and into a simple loincloth. The cool touch of the marble against his skin offers instant relief from the heat outside. Here, surrounded by familiar faces, Lucius feels the camaraderie that comes with communal bathing—men from all walks of life, from wealthy merchants to freedmen, share this daily ritual.

After lingering in the tepidarium, Lucius moves to the caldarium, the hot room. This chamber, heated by an ingenious system of hypocausts—an underfloor heating system that circulates hot air—feels like stepping into an oven. The caldarium is the heart of the bathing ritual, where the intense heat opens pores and cleanses the body.

Steam rises from a large hot-water pool, and Lucius immerses himself, feeling the tension in his muscles melt away. He takes up a strigil, a curved metal tool, and scrapes the oil and sweat from his skin, a cleansing ritual that leaves him feeling refreshed. Around him, men sit on marble benches, beads of sweat glistening on their brows, engaging in animated conversations. In this communal space, barriers of rank seem to disappear, if only temporarily, as all are united in the pursuit of relaxation.

Once Lucius has had his fill of the heat, he moves to the final stage of the bath, the frigidarium—the cold room. The frigidarium is a stark contrast to the caldarium, with its cold plunge pool offering a bracing shock to the system. The water is cool and invigorating, closing the pores and bringing a sense of revitalization. Lucius dives into the pool, the chill cutting through the lingering heat, refreshing his body and mind. This final stage of the bathing process leaves him feeling renewed, ready to face the remainder of the day.

Before leaving, Lucius returns to the apodyterium, where he dries off and dresses in his tunic once again. The baths, though a part of the daily routine, are a luxurious escape—a place where the cares of the day are momentarily forgotten in the soothing embrace of hot and cold waters.

Afternoon in Pompeii: Main Meal and Leisure Time

Refreshed from his time at the baths, Lucius makes his way home, his body cleansed and his mind relaxed. The streets are quieter now as the heat of the afternoon settles over Pompeii, and many residents retreat indoors for their main meal of the day, the cena.

When Lucius arrives, the enticing aroma of food fills his home. His wife, Aemilia, has prepared a meal that reflects the resources of their coastal town and the Mediterranean diet: fresh bread, seasoned olives, salted fish caught from the nearby Bay of Naples, and a thick stew made from vegetables and pulses like lentils and beans. This stew, likely flavored with herbs such as thyme, rosemary, and bay leaves, would be a simple but hearty dish—one that was common among middle-class Roman families. A clay jar of garum, the fermented fish sauce beloved by the Romans, sits on the table, ready to enhance the flavors of the meal.

The family gathers in their triclinium, the formal dining room, where they dine in the Roman style—reclining on couches around a low, rectangular table. This posture, known as recumbency, is a mark of status and comfort in Roman society, traditionally adopted by the wealthy but also embraced by the upwardly mobile middle class, like Lucius and his family. Reclining while eating is seen as a leisurely indulgence, a signal that one has the luxury to savor their meal and the conversation that accompanies it. Their young son, Tiberius, though still too young to recline in the traditional manner, sits at the edge of the table, eager to join the adult discussion.

As they enjoy their meal, Lucius and Aemilia exchange the events of their day. Lucius shares stories from the market while Aemilia recounts her visit to the nearby Temple of Venus, Pompeii’s patron goddess, where she offered prayers and sacrifices for the prosperity of their household. Tiberius, brimming with excitement, interrupts to talk about the upcoming gladiatorial games at the amphitheater, describing the animals he’s heard would be featured in the grand hunt. For the Romans, these spectacles of blood and valor were not just a form of entertainment, but also a reminder of their dominion over nature and the distant reaches of the empire.

Wine, a staple of Roman life, is served freely throughout the meal. However, in typical Roman fashion, it is diluted with water, a practice meant to temper its potency and reflect moderation. The wine is local, likely produced in the surrounding vineyards of Campania, renowned for its rich volcanic soil that imparts a distinct flavor to the grapes. As the conversation flows, so too does the wine, making the afternoon feel languid and unhurried.

After the meal, Lucius and his family retire to their modest but beautiful garden, a central feature in many Pompeian homes. Surrounded by the walls of the house, the hortus offers a tranquil sanctuary, with a small fountain at its center that trickles cool water into a stone basin. This simple water feature not only brings relief from the heat but also symbolizes wealth and status, as private fountains were considered a luxury.

Around the fountain, fig trees, pomegranates, and flowering vines flourish, their rich colors and scents adding to the serene atmosphere. The garden is not just a place of leisure but also a spiritual space, where small household shrines often stand, honoring the Lares—the guardian deities of the home. For a brief time, the world outside fades, and he is enveloped by the simple pleasures of home—his family, his garden, and the cool shade that provides relief from the intense afternoon sun.

As the afternoon wears on, Lucius knows that soon the streets will come alive again, with Pompeii’s citizens emerging from their homes to continue the day’s business or gather for evening festivities. But for now, he enjoys the tranquility, the subtle joy of a well-spent afternoon shared with those closest to him.

Late Afternoon: Civic Engagement and Socializing in Pompeii

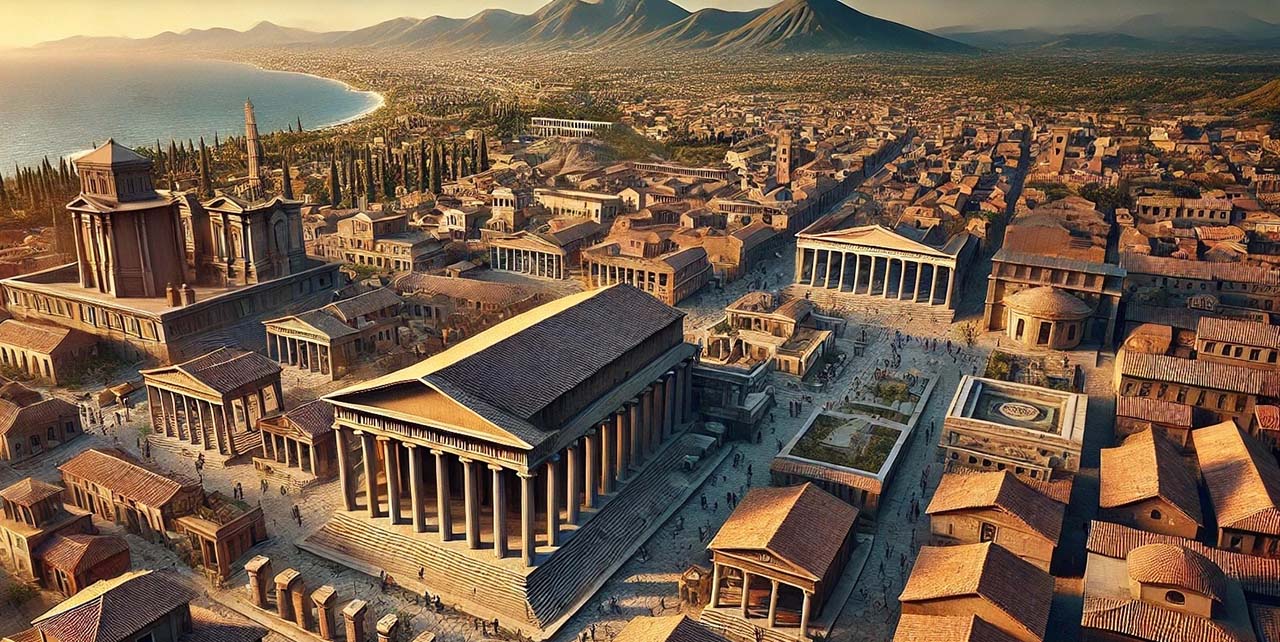

In the late afternoon, Lucius heads to the Forum, the political and social heart of Pompeii. The Surrounded by key public buildings such as the basilica (the town’s courthouse), the towering Temple of Jupiter, and the macellum (the main food market), it’s the focal point for political, commercial, and religious activity.

The broad, open square is alive with movement as citizens of all classes—merchants, farmers, freedmen, and even slaves—conduct their business or simply socialize. Stalls in the macellum sell everything from fresh fish to spices, while vendors hawk their wares to passersby. The colonnaded walkways around the square provide shelter from the sun for those engaged in more official matters. Here, statues of local dignitaries and emperors stand as reminders of the Roman virtues of duty and honor, silently overseeing the daily life of Pompeii.

Today, Lucius attends a meeting of the town council at the basilica. While he himself holds no political office, he is a concerned and active citizen, and Roman society encourages civic participation at every level. The local magistrates and council members—elected men of stature in the community—debate various pressing issues, such as the maintenance of roads, the building of aqueducts, and the planning of upcoming religious festivals.

Religious observances are a crucial aspect of public life, as pleasing the gods is believed to ensure the town’s continued prosperity. Lucius listens attentively, understanding that even as a merchant, these decisions will impact his business, his taxes, and his social standing.

The debate is lively, as it often is when discussing matters of public funds and taxes. The Roman ideal of public service is on full display as the local leaders argue about the best ways to allocate resources and ensure the town’s infrastructure is maintained. The Forum is filled with the sounds of orators delivering impassioned speeches, citizens debating with their neighbors, and political candidates hoping to sway opinions for future elections. The power of rhetoric in Roman life cannot be overstated, and Lucius, though not a politician, admires the art of persuasion used by the speakers.

After the meeting, Lucius exits the basilica and moves toward a thermopolium, one of the many popular taverns scattered throughout Pompeii. These wine bars, easily identified by their marble counters inset with large jars (dolia) for storing food and drink, serve as informal social hubs where people from all walks of life can gather. Here, the atmosphere is lively—voices rise in animated conversation, and the clinking of cups adds a musical undertone to the general din.

Lucius greets a few friends, fellow merchants who, like him, have finished their day’s work and seek a place to unwind. They gather around a small table, where they are served wine diluted with water, following Roman custom. The conversation flows as freely as the wine, covering everything from the state of the olive harvest to the political intrigues of the empire. Talk of the upcoming gladiatorial games stirs excitement, with Lucius and his companions speculating on which gladiators will face off and what animals might be featured in the hunts.

As they sit, they share light snacks of olives, bread, and salted nuts, common fare in such establishments. The thermopolium is a mix of all classes—merchants, craftsmen, and laborers—and the convivial atmosphere makes it easy to form new friendships. Strangers become quick allies over shared cups of wine, swapping stories of their lives and their travels. Despite the social stratifications of Roman society, places like this offer a chance for people to mingle outside their usual circles.

The conversation eventually turns to the strange tremors that have been unsettling Pompeii in recent days. While most dismiss them as minor disturbances, a few voices express concern that the tremors may be a sign of divine displeasure. Lucius, like many, doesn’t give the rumors much thought. After all, Mount Vesuvius has slept for centuries, and there is little reason to believe that would change now. He brushes off the superstitions with a smile, preferring to focus on more immediate concerns.

The late afternoon wears on, and as the sun begins to set, the Forum and surrounding streets glow with the warm light of dusk. After finishing his drink and bidding his companions farewell, Lucius prepares to return home, the shadows lengthening over the Forum as another day in Pompeii draws to a close.

Evening: Entertainment and Family Time

As they stroll further, the occasional roar of a wild animal breaks the calm from the direction of the amphitheater. The amphitheater, where gladiatorial games and wild animal hunts are held, houses a variety of beasts for the next day’s events. Tiberius, always fascinated by the idea of seeing lions, leopards, and bears, pulls his father’s arm, asking to visit the amphitheater the following day to watch the spectacle.

Their walk takes them past some of Pompeii’s grand villas, where the wealthy elite host private evening dinners and gatherings. The sound of laughter and conversation spills over the garden walls, where lanterns light up the lavish gardens inside. These dinners, or convivia, are exclusive social affairs, where the rich and powerful dine on exotic foods, recline on couches, and discuss matters of business, politics, and culture in a more intimate setting.

For families like Lucius’, however, the public spaces of Pompeii offer plenty of free entertainment. After their stroll, they return to their home, where the cool night breeze and the peaceful sound of their garden fountain offer a tranquil retreat. Lucius relaxes with a final cup of watered win while Aemilia tends to their modest garden of herbs, fruit trees, and flowering vines. Tiberius is still buzzing with excitement from the evening’s events, already imagining the next day’s adventure at the amphitheater.

Nighttime in Pompeii – Resting Under Vesuvius’ Gaze

As the evening turns into night, Lucius and his family return home. The house is quiet now, the lamps casting a warm glow on the walls decorated with colorful frescoes.

Before bed, Lucius spends some time at the household shrine. Kneeling before the shrine, Lucius lights a small incense offering and whispers a prayer of gratitude to the household gods. The flickering flame illuminates the statuettes of the Lares and Penates, along with other symbols of divine protection. He thanks them for the day’s blessings, from the success of his market dealings to the laughter shared with his family at the theater, and humbly asks for their continued guidance and protection over his household.

The town, once bustling with activity, is now quieter—save for the occasional bark of a dog in the distance, the soft murmur of late-night revelers passing through the streets, and the faint whisper of the sea breeze from the nearby coast. These sounds have become part of the comforting rhythm of life in Pompeii.

As Lucius closes his eyes, his thoughts drift to the day that has passed. He reflects on the small victories of the day, the camaraderie with friends at the thermopolium, the joy of his son’s excitement for the upcoming games, and the contentment that comes from knowing his family is safe and well under the watchful eye of Mount Vesuvius.

Little does Lucius know that in a matter of weeks, the peaceful routine of Pompeii will be shattered. The eruption of Vesuvius will bury the town in ash and pumice, preserving it for centuries as a snapshot of Roman life. But tonight, the future is unknown, and Lucius falls asleep, content in the knowledge that tomorrow will bring another day of life in Pompeii.

This imagined journey through a day in Pompeii offers a glimpse into the everyday experiences of its inhabitants, highlighting the rhythms of life in this ancient town. Pompeii was a place of culture, commerce, and community, where the simple pleasures of daily life were enjoyed to the fullest, even as the looming shadow of disaster unknowingly grew larger by the day. By exploring this past, we not only honor the memory of those who lived there but also gain a deeper understanding of the human experience that transcends time.